Scheme Intro

Practical Session - Week 3 PPL@BGU

In this session, we review:

- Dr. Racket (Scheme)

- Atomic expressions

- Compound expressions

- Primitives in Scheme

- Design by Contract

- Types

- Iterative Functions and Recursive Functions

Introduction to DrRacket

In the following practical sessions, we will use the programming language Scheme. We use the Racket interpreter of Scheme. Program files in Racket are saved with extension *.rkt.

You should install DrRacket software as explained in Useful Links

The first time you open DrRacket, you should:

- Choose a language: Choose Language -> Language -> choose ‘Use the language declared in the source’.

- Close the software and run it again.

- All the files should start with the line:

#lang racket

Atomic Expressions

Scheme expressions are evaluated by the Interpreter, which computes the expression’s value.

Atomic expressions are expressions that do not consist of other sub-expressions. There are several atomic expression types:

- Numbers

> 3 3 > 3.75 3.75 - Booleans:

> #t #t > #f #f - Primitive procedures:

Primitives get their values from the programming language (in our case Scheme).

> + #<procedure:+> > not #<procedure:not> > eq? #<procedure:eq?>

(> is the Interpreter’s prompt.)

Compound Expressions (not atomic)

Compound expressions are expressions that contain nested expressions.

In Scheme, these expressions are all marked using parentheses ( ).

Scheme’s syntax is based on prefix notation, which means the procedures (operator) appear before their arguments (operands) in compound expressions. For example:

> (- 25 5)

20

> (number? 3.75)

#t

> (> (* 4 3) (/ 4 2))

#t

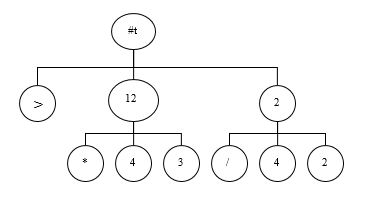

How Compound Expressions are Evaluated

- evaluate the sub-expressions recursively

- apply the value of the operator on the values of the operands

We can represent that evaluation in an evaluation tree:

Abstraction

We can give names to values of expressions by using a define expression. For example:

> (define pi 3.14159)

> (define radius 10)

Pay attention! define is a special form: it is a compound expression which is not evaluated like regular compound expressions.

If we evaluate define in standard way, then the variable radius would have to be evaluated - which would lead to an error, (because the whole point of define is to give a value to the variable!).

Interpreter Operation - (define var exp)

- evaluate the expression

exp - add the variable

varand the value to the global environment - it is called a binding between the variable and the value.

> pi

3.14159

> (* pi (* radius radius))

314.159

> (define perimeter (* 2 pi radius))

> perimeter

62.8318

Note: the evaluation of a define form does not return any value.

Note: in our course, we do not allow nested define expressions (that is expressions where define appears embedded inside other expressions).

Primitives in Scheme

We will introduce Scheme primitives as we go.

Note that in contrast to JavaScript, primitives in Scheme are strongly typed: they expect a specific type as argument, and they throw an error at runtime when they are passed a parameter which does not match the expected type.

> (+ 1 #t)

+: contract violation

expected: number?

given: #t

argument position: 2nd

other arguments...:

1

As a starting point, the following primitives are all numeric primitives - that is, their type is [Number * Number -> Number]: +, *, -, /

The following procedures are numeric predicates - that is their type is [Number * Number -> Boolean]: <>, <, >=, <=, =

(Note: most primitives in Scheme can take a variable number of parameters as in (+ 1 2 3).)

Procedure Type

We can define new user procedures (not primitive) by using lambda expressions, which is also a special form:

(lambda <formal-parameters> <body>)

> (lambda (rad) (* pi rad rad))

#<procedure>

lambda is a value constructor of procedures.

The value of a lambda expression is called closure. Remember to distinguish between syntax (lambda expression) and semantics (closure value).

lambda defines anonymous procedures:

> ((lambda (rad) (* pi rad rad)) 10)

314.159

In this example, rad is a formal parameter of the anonymous procedures. The value 10 is an argument for this procedure.

To compute the application of a closure to parameters, the interpreter replaces every occurrence of the formal parameter rad in the body of the function with the value 10.

We can combine a define expression with lambda expressions to define named procedures:

> (define average

(lambda (x y)

(/ (+ x y) 2)))

> average

#<procedure:average>

Procedures Summary

The definition of a procedure consists of:

- formal parameters

- body - list of expressions

Example 1:

(define average1

(lambda (x y)

(+ x y)

(/ (+ x y) 2)))

The return value of the procedure above is the last expression. The previous expressions are evaluated and the Interpreter ignores them.

So why do we allow multiple expressions in the body of a procedure? When is it useful?

Example 2 - procedure with side effects:

(define average2

(lambda (x y)

(display x)

(+ x y) ;; Useless in this context

(newline)

(display y)

(newline)

(/ (+ x y) 2) ;; Return value of the procedure

))

The variables display and newline denote Scheme primitives.

The return value of display and newline expressions is void, but they have a side effect - they print to stdout.

(void is a special value which is used in Scheme to indicate the returned value is of no importance - it is returned by the (void) procedure).

The expression (+ x y) is unnecessary, because it does not have a side effect and is in the middle of the sequence of expressions.

The semantics of the execution of the body is to execute all the expressions in sequence - in the order in which they occur in the body.

Order is important because of the side-effects. Sequence is only meaningful when there are side-effects.

Functional Equivalence

Definition: Two procedures are functionally equivalent if and only if they either: enter into an infinite loop on the same inputs, or throw exceptions on the same inputs, or halt on the same inputs and return the same value on these parameters.

Question 1: Are the procedures average1 and average2 functionally equivalent?

Question 2: look at the following procedure:

(define addition (lambda (x y)

(+ x y)

(display 'ok)))

> (addition 2 4)

ok

What should be the value of the expression?

> (void? (addition 2 4))

ok#t

What is the return value?

(addition 2 (addition 3 5))

Design By Contract

When writing procedures, we follow the Design by Contract methodology.

Practically, this means we first specify the contract that the procedure must enforce. We document it as a formatted set of comments before the procedure definition:

; Signature: area-of-ring(outer,inner)

; Purpose: To compute the area of a ring whose radius is

; ’outer’ and whose hole has a radius of ’inner’

; Type: [Number*Number -> Number]

; Example: (area-of-ring 5 3) should produce 50.24

; Pre-conditions: outer >= 0, inner >= 0, outer >= inner

; Post-condition: result = PI * outer^2 - PI * inner^2

; Tests: (area-of-ring 5 3) ==> 50.24

Signature specifies the name of the procedure, and its parameters.

Purpose is a short textual description.

Type specifies the types of the input parameters and of the returned value. The types of number-valued and boolean-valued expressions are Number and Boolean, respectively. The type of a procedure is denoted:

[(type of arg1) *...* (type of argn) –> (return type)].

Example gives examples of procedure applications and their expected return values.

Pre-conditions specify conditions that the input parameters are obliged to satisfy - beyond those expressed by the type.

Post-conditions specify conditions that the returned value is responsible to satisfy.

Tests provide test cases.

For important procedures, it is good practice to include all of these fields in the contract.

For all procedures, we require in all Scheme code produced in the class to have at least these 3 components:

; Signature: area-of-ring(outer,inner)

; Purpose: To compute the area of a ring whose radius is

; ’outer’ and whose hole has a radius of ’inner’

; Type: [Number*Number -> Number]

If the pre-condition is not trivial (that is, always true), then you must specify it as well.

For example:

; Signature: fact(n)

; Type: [Number -> Number]

; Purpose: compute the factorial of n.

; Pre-conditions: n is a natural number

; Tests: (fact 5) => 120

(define fact

(lambda (n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (fact (- n 1))))))

If there are no pre-conditions, you should write true.

The programmer of the procedure should not check the pre-conditions - it is the responsibility of the client to make sure pre-conditions are met before calling the procedure.

The central idea of DbC is a metaphor on how elements of a software system collaborate with each other, on the basis of mutual obligations and benefits. The metaphor comes from business life, where a client and a supplier agree on a contract. The contract defines obligations and benefits. If a routine provides a certain functionality, it may:

- Impose a certain obligation to be guaranteed on entry by any client module that calls it: The routine’s precondition – an obligation for the client, and a benefit for the supplier.

- Guarantee a certain property on exit: The routine’s post-condition is an obligation for the supplier, and a benefit for the client.

- Maintain an invariant.

The contract is the formalization of these obligations and benefits.

The separation of responsibilities between caller and implementer of the procedures is:

---------------------------------------------------------------------

| Client Supplier

------------|--------------------------------------------------------

Obligation: | Guarantee precondition Guarantee post-condition

Benefit: | Guaranteed post-condition Guaranteed precondition

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Compound Types

In Scheme, we will use two compound types (others exist in Scheme, but we restrict ourselves to these 2 types):

- Pair type

- List type

Pair Type

A pair value combines 2 values into a single unit.

For values a (of type T1) and b (of type T2), we create a new value (of type Pair(T1,T2)) with the value constructor “cons”:

(cons a b)

The type of the return value is Pair(T1,T2).

Procedures on the Pair type:

- cons Type: [T1 * T2 -> Pair (T1, T2)]

- getters:

- car: Type: [Pair(T1, T2) -> T1]

- cdr: Type: [Pair(T1, T2) -> T2]

- predicates:

- pair?: Type: [Any -> Boolean]

For example:

> (cons 1 #t)

'(1 . #t)

The type of the return value is Pair(Number,Boolean).

Note: (cons 1 #t) is a syntactic form - the application of a primitive operator to 2 arguments - ‘(1 . 2) is the semantic value.

Scheme also provides a syntactic form to represent literal compound values of type Pair. It is:

'(1 . #t) ;; starts with the quote symbol - followed by a parenthesis and `.` between the first and second member of the pair.

When a pair is embedded as the second member of a pair, the literal form in Scheme is changed.

> (cons 1 (cons 2 3))

;; instead of '(1 . (2 . 3)), it happens because DrRacket does not know

;; if it prints pair of pairs or list (see later), until it's too late

'(1 2 . 3)

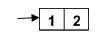

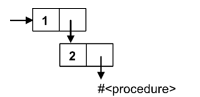

Box Representation - Pair and Cons-cells

Traditionally, pairs are represented graphically as rectangles split in two halves. These rectangles are called cons cells - they help understand the structure of compound recursive pair structures.

For people with C++ background, it helps to think of a cons-cell (a pair) as 2 pointers to other values.

Example 1:

> (cons 1 2)

'(1 . 2)

Example 2:

> (cons 1 (cons 2 (lambda () (+ 1 2))))

'(1 2 . #<procedure>)

We can use compound accessors to traverse recursive pairs.

These are convenient abbreviations of combinations of car and cdr: the cdd...dr procedures (maximum 4-d):

> (define c (cons 1 (cons 'cat (cons 3 (cons 4 5)))))

> c

'(1 cat 3 4 . 5)

> (cdddr c)

'(4 . 5)

> (cdr (cdr (cdr c)))

'(4 . 5)

> (caddr c) ;; equivalent to (car (cdr (cdr c)))

3

List Type

The type List is defined inductively:

- an empty list is a list - ‘() or (list)

- a pair where the second argument is a list, is a list

It helps to define List(T) as Union(EmptyList, NEList(T)) [NEList(T) are the non empty list values]. It also helps to define heterogeneous lists types as Union(EmptyList, NEList) [NEList are the non empty heterogeneous list values].

We distinguish:

- homogeneous list - all members are the same type T - List(T)

- heterogeneous list - members with different types - List

list - is a value constructor (to create a list). This procedure is a variadic (it can get any number of parameters).

In particular, (list) returns the empty list.

'() also denotes the empty list.

cons - is a value constructor too.

List primitives:

- list Type: [T * T …. -> List(T)]

- cons Type: [T * List(T) -> NEList(T)]

- getters:

- car: Type: [NEList(T) -> T]

- cdr: Type: [NEList(T) -> List(T)]

- predicates:

- list?: Type: [Any -> Boolean]

- empty?: Type: [Any -> Boolean]

NOTE: We use the same cons primitive as for pairs - but we think of it as a primitive with a different type.

> (list)

'()

> '()

'()

> (list 1 2)

'(1 2)

> (cons 1 2)

'(1 . 2)

> (list 1 2 3)

'(1 2 3)

> (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 '())))

'(1 2 3)

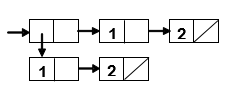

Box Representation - List

> (list (list 1 2) 1 2)

'((1 2) 1 2)

Atomic / Compound Values and Equality Testing

To test whether 2 values are equal, there are multiple predicates in Scheme.

- (= n1 n2) only works for numeric arguments.

- (eq? v1 v2) - compares addresses

- (equal? v1 v2) - compares values

- There is no way to test that 2 functions are equal (why?)

> (= 1 1)

#t

> (= 1 2)

#f

> (= #t #t)

=: contract violation

expected: number?

given: #t

argument position: 1st

other arguments...:

#t

> (eq? 1 1)

#t

> (eq? 1 2)

#f

> (eq? #t #t)

#t

> (eq? #t '(1 2))

#f

> (eq? '(1 2) '(1 2))

#f

> (define l12 (list 1 2))

> (eq? l12 l12)

#t

> (equal? 1 1)

#t

> (equal? 3 3.0)

#f

> (equal? '(1 2) '(1 2))

#t

Structure of Procedures Operating on Lists

The general recipe for a procedure that operates on Lists follows the inductive definition of the type:

(define <recipeOnList>

(lambda (listOfT)

(if (empty? listOfT)

;; base case

do if true

;; recursive case

do if false)))

Let us analyze examples of this recipe:

Question 1:

Write the procedure remove:

; Signature: remove(x lst)

; Type: [T * List(T) -> List(T)]

; Purpose: remove the first appearance of x in lst

; Pre-conditions: true

; Tests: (remove 2 (list 1 3 2 2)) => '(1 3 2)

(define remove

(lambda (x lst)

(if (empty? lst)

lst

(if (equal? (car lst) x)

(cdr lst)

(cons (car lst) (remove x (cdr lst)))))))

Question 2:

Write the procedure remove-all:

; Signature: remove-all(x lst)

; Type: [T * List(T) -> List(T)]

; Purpose: remove all the occurrences of x in lst

; Pre-conditions: true

; Tests: (remove-all 2 (list 1 3 2 2)) => '(1 3)

(define remove-all

(lambda (x lst)

(if (empty? lst)

lst

(if (equal? (car lst) x)

(remove-all x (cdr lst))

(cons (car lst) (remove-all x (cdr lst)))))))

We saw in the lecture the procedure filter:

; Signature: filter(pred,lst)

; Type: [ (T->Boolean) * List(T) -> List(T) ]

; Purpose: Return the list of elements in lst that satisfy pred.

(define filter

(lambda (pred lst)

(if (empty? lst)

'()

(if (pred (car lst))

(cons (car lst) (filter pred (cdr lst)))

(filter pred (cdr lst))))))

Question 3: Write the procedure remove-all using filter:

; Signature: remove-all(x lst)

; Type: [T * List(T) -> List(T)]

; Purpose: remove the all appearances of x in lst

; Pre-conditions: lst is a list

; Tests: (remove-all 2 (list 1 3 2 2)) => '(1 3)

(define remove-all

(lambda (x lst)

(filter (lambda (y) (not (equal? x y)))

lst)))

> (remove-all 1 '(1 2 1 3 1))

'(2 3)

> (remove-all '(a b) '((a 1) (a 2) (a b) (a 3) (a b)))

'((a 1) (a 2) (a 3))

Question 4: Can we write the procedure remove using filter?

No - the decision implemented in filter is independent of the other decisions taken on the list. Remove requires us to take a different decision depending on the decisions already taken.

Question 5: Write a procedure that finds a pair in a list of pairs by the value of the first element.

Let us define a data type that is similar in functionally to Maps in JavaScript: a list of pairs. Traditionally, this is a called an association list in Scheme - or in short AList.

AList(T1, T2) = List(Pair(T1,T2))

We think of an AList as a list of values of type T2 indexed by keys of type T1. For example:

;; AList(Number,Number)

'((1 . 10) (2 . 20) (3 . 30))

;; AList(Boolean,Number)

'((#t . 1) (#f . 0))

; Purpose: find a value in an AList given its key.

; Signature: alist-get(alist, key)

; Type: [AList(T1,T2) * T1 -> T2 | '()]

(define alist-get

(lambda (alist key)

(if (empty? alist)

'()

(if (equal? (caar alist) key)

(cdar alist)

(alist-get (cdr alist) key)))))

> (alist-get '((1 . 10) (2 . 20) (3 . 30)) 2)

20

> (alist-get '((1 . 10) (2 . 20) (3 . 30)) 0)

'()

Can you define alist-get using filter?

Let Expression

A let expression gives us the ability to define local variables.

> (let ((a 5) (b 6))

(+ a b))

11

Be careful that the values of the variables are computed outside the scope of the variables:

> (let ((a 1)

(b (* a 3)))

(+ a b))

Error: a: undefined; cannot reference an identifier before its definition

Iterative and Recursive Functions

We need to implement the function ‘exp’:

; Signature: exp(b e)

; Type: [Number * Number -> Number]

; Purpose: to calculate b to the power e.

; Pre-conditions: b >= 0, e is natural.

; Tests: (exp 2 3) => 8

; (exp 2 4) => 16

; (exp 3 4) => 81

Question 1: write a recursive version

(define exp

(lambda (b e)

(if (zero? e)

1

(* b (exp b (- e 1))))))

Question 2: write an iterative version of exp

;; Purpose: compute b^e in an iterative manner

;; Signature: exp-iter(b,e,1)

;; Type: [Number * Number * Number -> Number]

;; Pre-conditions: e is a natural number

;; Example: (exp-iter 2 10 1) => 1024

(define exp-iter

(lambda (b e acc)

(if (zero? e)

acc

(exp-iter b (- e 1) (* b acc)))))

This version is iterative because the call to exp-iter is in tail position.

It is a different algorithm than the one shown above.

We can use the trace function of Racket to see exactly how a recursive function runs vs. an iterative function:

(require racket/trace)

(define exp ...)

(define exp-iter ...)

(trace exp)

(trace exp-iter)

> (exp 2 5)

>(exp 2 5)

> (exp 2 4)

> >(exp 2 3)

> > (exp 2 2)

> > >(exp 2 1)

> > > (exp 2 0)

< < < 1

< < <2

< < 4

< <8

< 16

<32

32

> (exp-iter 2 5 1)

>(exp-iter 2 5 1)

>(exp-iter 2 4 2)

>(exp-iter 2 3 4)

>(exp-iter 2 2 8)

>(exp-iter 2 1 16)

>(exp-iter 2 0 32)

<32

32

We can see in the call to exp that we need to keep track of the previous stack frames, which creates a “pyramid” stack trace. This is in contrast to the iterative exp-iter which creates a linear stack trace.

Question 3: write an iterative version

;; secondary function

(define exp$

(lambda (b e delayed)

(if (zero? e)

(delayed 1)

(exp$ b (- e 1)

(lambda (res-e-1) (delayed (* res-e-1 b)))))))

;; the main function

(define exp

(lambda (b e)

(exp$ b e (lambda (x) x))))

Why is exp$ considered iterative? because the last call is exp$.