TypeScript: Type Checking

PPL 2023

Practical Session - Week #2

Why Types

Adding types to a program has two key advantages:

- It allows the compiler to detect errors that would otherwise only be detected at runtime. It is much better to detect errors as early as possible in the development cycle.

- It serves as excellent documentation by reflecting the intention of the programmer.

Types also help programmers structure the code they write so that it follows the structure of the data it processes.

In this session, we review:

- the syntax of type annotations in TypeScript

- analyze an example of recursive type definition with the corresponding operations

- analyze how the type of functions is derived

Types in TypeScript

TypeScript adds optional type declarations to JavaScript. The principles of this addition are:

- Type declarations are optional. If they are present, they are checked, otherwise no check is performed. This means that regular JavaScript with no type annotations at all are valid TypeScript expressions.

- The TypeScript compiler performs two tasks:

- It translates a TypeScript program into a JavaScript program

- It checks that the program satisfies all the type declarations specified in the program.

- Type annotations can be implicit and inferred by the TypeScript compiler.

// This TypeScript program

function add(a: number, b: number): number {

return a + b;

}

add(1, 3); // ==> 4

// is translated by `tsc` into this JavaScript program:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

add(1, 3); // ==> 4

Type Annotations

Type annotations are optional in TypeScript. They can occur in the following contexts:

// After variable declarations

let varName: <typeAnnotation>;

// As part of a function signature

function fname(param : <typeAnnotation>, ...) : <typeAnnotation> { ... }

// With fat arrow notation for functions

(param: <typeAnnotation>, ...): <typeAnnotation> => ...

Type annotations are written in a specific form - which we call the type language. The type language is used to describe the expected type of variables, parameters or the values returned by functions.

The simplest type language expression refers to an atomic type - for example number, boolean, string.

More complex type language expressions are needed to describe types over compound values.

Array Type Expressions - Homogeneous Array

let numberArr : number[] = [1, 2, 3];

let num: number = numberArr[0];

console.log(num); // ==> 1

One may use the notation Array<T> instead of T[].

Map Type Expressions

To describe map types, the following notation is used:

{ <key>: <typeAnnotation>; ... }

For example:

let s: { name: string, cs: boolean, age: number } = { name: "avi", cs: true, age: 22 };

s; // => { name: 'avi', cs: true, age: 22 }

Named Type Expressions

Type expressions can be given names.

Type expressions can be named using the type alias construct:

type <typeName> = {

<key>: <typeAnnotation>;

...

}

Or in general, to give a name to any type annotation:

type <typeName> = <typeAnnotation>;

type Student = {

name: string;

cs: boolean;

age: number;

}

let s: Student = { name: "avi", cs: true, age: 22 };

s; // => { name: 'avi', cs: true, age: 22 }

Recursive Types

Naming types allows the definition of recursive types. Consider the case of defining a Linked List of numbers:

type NumberLink = {

num: number;

next?: NumberLink;

}

let lst1: NumberLink = {

num: 1,

next: {

num: 2,

// The last element does NOT have a next field.

next: { num: 3 },

}

};

lst1; // => { num: 1, next: { num: 2, next: { num: 3 } } }

Operations over Recursive Types

This type definition is recursive - we observe that the definition of the NumberLink uses the NumberLink type as a component of its own definition. This type annotation defines a set of values. Think of this set of values as the set of values which are map with a mandatory key num with a number value and a next key which can either not occur, or when it occurs must be of type NumberLink.

This recursive type, thus, defines a set of embedded values - down to a terminal case, where the next key is not defined, and the embedding stops.

Given this type recursive definition, we can define procedures to traverse the linked list from start until a condition is met or until we reach the end of the list. The following function illustrates the method:

const printNumberLinkedList: (list: NumberLink) => void = list => {

// We know list.num is a number

console.log(list.num);

// list.next can either be undefined or a NumberLink

if (list.next === undefined) {

console.log("end of list");

} else {

// It is safe to pass a NumberLink value

// to the recursive call

printNumberLinkedList(list.next);

}

};

printNumberLinkedList({ num: 1, next: { num: 2, next: { num: 3 } } });

// ==>

// 1

// 2

// 3

// end of list

The structure of the function follows the type definition - when the function receives a value of type NumberLink, it knows

it is a map value, that must contain a num key which must be of type number. It is thus safe to invoke list.num and to expect a number value.

Then when we need to access the next key - the type definition indicates we may find 2 different configurations:

- Either

nextis not present - in which case,list.nextwill return theundefinedvalue. - Or

nextis present and it must be a value of type NumberLink.

The code enumerates these options according to the type definition, and specifies what operations are possible according to the structure of the data that we process.

Generic Types

Consider the case of defining an homogeneous generic Linked List. This is an abstraction over the previous type definition - we make the type of the values in the linked list a type variable. This is indicated by the <T> component in the type annotation.

type Link<T> = {

x: T;

next?: Link<T>;

}

let lst2: Link<string> = {

x: "avi",

next: { x: "bob", next: { x: "charles" } }

};

lst2; // ==> { x: 'avi', next: { x: 'bob', next: { x: 'charles' } } }

The type variable, T, can be replaced with a compound type as well:

let lst3: Link<{ name: string }> = {

x: { name: "xx" },

next: { x: { name: "yy" }, next: { x: { name: "last" } } }

};

lst3; // ==> { x: { name: 'xx' }, next: { x: { name: 'yy' }, next: { x: [Object] } } }

Consider the case of defining an heterogeneous Linked List, we can use the special type called any - which denotes the set of all possible values that can be computed by the language:

let lst4: Link<any> = {

x: "hi",

next: { x: 1, next: { x: "bye" } }

};

lst4; // ==> { x: 'hi', next: { x: 1, next: { x: 'bye' } } }

How can we write a function that operates over a generic data structure such as Link<T>?

Does the function need to know the type T to be useful at all?

There are three ways when it can be relevant to write an operation over a generic type:

- Either the operation does not depend on knowledge of the type which is contained;

- Or the operation itself is a generic function which can be applied to a variety of types.

- Or we write an operation that is only applicable for a specific instance of the generic type.

Let us see an example of each case: a function which counts how many elements are in a Linked List does not depend on the type of the elements in the list. We can write it as follows:

const countLink: <T>(list: Link<T>) => number = (list) => {

return list.next === undefined ? 1 : 1 + countLink(list.next);

};

countLink({ x: "hi", next: { x: "hello", next: { x: "bye" } } }); // => 3

Note how the type of the function must also be marked as a generic function - since it can be applied to parameters for any type T. This is noted with the notation:

<T>(list: Link<T>) => number;

For the second case, consider the case of the primitive function console.log() - it can receive parameters of any type.

In this case, we can write a function that operates over the elements in the list even if they are of different types:

const printLink: <T>(list: Link<T>) => void = (list) => {

console.log(list.x);

list.next === undefined ? console.log("end of list") : printLink(list.next);

};

printLink({ x: "hi", next: { x: "hello", next: { x: "bye" } } });

// ==>

// hi

// hello

// bye

// end of list

printLink({ x: 1, next: { x: 2, next: { x: 3 } } });

// ==>

// 1

// 2

// 3

// end of list

Note that in the two invocations of the generic functions above, the compiler guesses the type of the parameter (Link<string> and Link<number>) from inspection of the literal.

The following invocation on a heterogeneous list, though, will not pass compilation:

printLink({ x: 1, next: { x: "a", next: { x: 3 } } });

This is because the compiler will not infer on its own that the programmer intends to use an any type or a type union.

To make this work, the programmer must explicitly indicate that this is what is intended as follows:

let l: Link<any> = { x: 1, next: { x: "a", next: { x: 3 } } };

printLink(l);

// ==>

// 1

// a

// 3

// end of list

The third option to operate over a generic data type, is to create a function which operates specifically over a type instance of the type variable T. For example, the following function operates only on List<number>:

const squareSumList: (list: Link<number>, acc: number) => number = (list, acc) => {

if (list.next === undefined) return acc + list.x * list.x;

else return squareSumList(list.next, acc + list.x * list.x);

};

squareSumList({ x: 1, next: { x: 2, next: { x: 3 } } }, 0); // = 1*1 + 2*2 + 3*3

// ==> 14

Recursive Types: Tree Variations

Trees with Arbritrary Number of Children

We saw in class the definition of a BinTree<T> type specification. It demonstrated:

- the need for naming types (with the

typealias construct) to allow recursive type specification - the need to define optional properties in maps (with the

key?notation) to allow the end of the recursion in the values.

Exercise: Define a Tree with an arbitrary number of children below each node.

type Tree<T> = {

root: T;

children: Tree<T>[];

}

// A tree of number nodes with just a root

let numbersTree: Tree<number> = {

root: 1,

children: []

};

// A tree of string nodes with just a root

let stringsTree: Tree<string> = {

root: "tirgul 2",

children: []

};

// A tree of numbers with one root and 2 children.

let t: Tree<number> = {

root: 1,

children: [

{ root: 2, children: [] },

{ root: 3, children: [] }

]

};

// A heterogeneous tree with string and number nodes

let anyTree: Tree<any> = {

root: "numbers and strings",

children: [numbersTree, stringsTree]

};

anyTree;

// ==>

// { root: 'numbers and strings',

// children:

// [ { root: 1, children: [] },

// { root: 'tirgul 2', children: [] } ] }

QUESTIONS:

In this case, we did not mark the field children as optional in the type definition.

It is children: [] and not children?: [] as it was in the case of BinTree or Link above.

What is the difference?

What are the arguments for and against defining children as optional?

ANSWERS

The question is related to the definition of the base case vs. inductive case in the recursive definition of the type.

- In the case of

BinTreeandLinkabove, we marked the base case with a key beingundefined. - In the case of

Treewith many children, we mark the base case with a key of typeTree[]being equal to[].

The decision of what is the base case is completely in the hands of the programmer - so both options are legitimate.

But we must aim for a situation where the base case is distinct from the inductive case - so that they can be easily distinguished when we write code that must decide whether we reached the end of the recursion. We must make sure as much as possible that the type definition we provide allows us to encode:

- All the possible values in the type

- Only the possible values in the type.

If we defined Tree as:

type Tree<T> = {

root: T;

children?: Tree<T>[];

}

we could still define all the possible values as requested. But the following two values would also be valid values of the type:

{ root:1, children: [] }

// and

{ root: 1 }

This means we would have two options to represent a leaf in a tree - which would mean it is an ambiguous representation. This would force us to test for the fact that a node is a leaf as follows:

if (root.children.length === 0) || (root.children === undefined) {

// ...

}

In this case, we prefer to have a non-ambiguous way to mark the base case - and write only:

if (root.children.length === 0) {

// ...

}

Thus, the definition of the type:

type Tree<T> = {

root: T;

children: Tree<T>[];

}

without the ? option is preferred.

Exercise: Create a function that follows a path within the tree and returns the node found at this place.

First, how do we encode a path in this tree?

A path must indicate a way to reach a specific node in the tree starting at the root and selecting one of the children at each step.

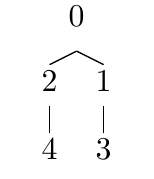

For example, let’s look at this tree:

type Tree<T> = {

root: T;

children: Tree<T>[];

}

const t: Tree<number> = {

root: 0,

children: [

{ root: 2, children: [{ root: 4, children: [] }] },

{ root: 1, children: [{ root: 3, children: [] }] }

]

};

We decide to encode paths as an array of numbers, indicating which child to select among the children of each node on the path:

the path of the child with {root:4} will be [0,0]

the path of the child with {root:3} will be [1,0]

the path of the child with {root:2} will be [0]

the path of the child with {root:1} will be [1]

We know the type of the tree, so we can design a function that will not give errors at runtime.

function getChild<T>(t: Tree<T>, path: number[]): Tree<T> {

if (path.length === 0)

// end of path

return t;

else if (t.children.length === 0)

// t is a leaf - cannot go down

return t;

else return getChild(t.children[path[0]], path.slice(1)); // recursive case

}

console.log(getChild(t, [0, 0])); // ==> { root: 2, children: [] }

console.log(getChild(t, [1, 0])); // ==> { root: 3, children: [] }

console.log(getChild(t, [1, 0, 0, 0])); // ==> { root: 3, children: [] } (Do not go "after" the leaves.)

In the rest of the semester, we write functions in TypeScript in the style of functional programming, using the fat arrow syntax. The same function will be defined as follows:

const getChild = <T>(t: Tree<T>, path: number[]): Tree<T> =>

// end of the path

(path.length === 0) ? t :

// t is a leaf - cannot go down

(t.children.length === 0) ? t :

// recursive case

getChild(t.children[path[0]], path.slice(1));

console.log(getChild(t, [1, 0]));

The differences are:

- The function is defined as a const name and an anonymous function on the right hand side of the const

- The body of the function is a single expression

- We use the ternary if expression (as opposed to the if-statement)

test ? then : else - There is no use for the

returnreserved word.

Function Types

Review:

Functions in Functional Programming languages are values - that is, we can write expressions, which when they are evaluated at run time become functions (more precisely, closures - since these values are functions that may capture variable bindings).

We must have the ability to describe the type of these values and distinguish among different types of functions.

An untyped function in Javascript has the following form:

// Named function (has global scope)

function add(x, y) {

return x + y;

}

// Anonymous function

const myAdd = function (x, y) {

return x + y;

};

// Using the fat arrow notation:

const myFatAdd = (x, y) => x + y;

myFatAdd(3, 5); // ==> 8

We can first specify the types of the parameters and the return type, in a way similar to the way it would be done in Java. This applies both to named functions and to anonymous functions.

// Named function

function addT(x: number, y: number): number {

return x + y;

}

// Anonymous function

const myAdd = function (x: number, y: number): number {

return x + y;

};

// Using the fat arrow notation:

const myFatAdd = (x: number, y: number): number => x + y;

myFatAdd(2, 4); // ==> 6

Let us now write the full type of the function out of the function value:

const myAdd: (x: number, y: number) => number = function (x: number, y: number): number {

return x + y;

};

const myFatAdd: (x: number, y: number) => number = (x: number, y: number): number => x + y;

myFatAdd(2, 7); // ==> 9

The type expression:

(x: number, y: number) => number;

is a function type. The values that this type denotes are functions that map a pair of numbers to a number - in other words, functions whose domain is within \(Number \times Number\) and whose range is within \(Number\). (Remember that types denote a set of values.)

This function type together with the name of the parameters is also called the function signature.

Function types include parameter names and parameter types and a return type. Parameter names are just to help with readability. We could have instead written:

const myAdd: (baseValue: number, increment: number) => number = function (x: number, y: number): number {

return x + y;

};

As long as the parameter types align, it’s considered a valid type for the function, regardless of the names you give the parameters in the function type.

The second part of the function type is the return type. We make it clear which is the return type by using a fat arrow (=>) between the parameters and the return type. This is a required part of the function type, so if the function doesn’t return a value (which means this is a function that just has a side-effect - no return value), we use the special type void instead of leaving it off.

Function Types Examples

1. Square Function

const square = x => x * x;

square(10); // ==> 100

The value of square is a closure.

The type of square is: (x: any) => number.

We infer that the return type of the function is number because the value of the function is that which is returned when computing its body; the body is an expression of the form x * x and the primitive operator * returns a number.

In scheme we would also infer that the x variable must be of type number because it appears as an argument of the * operator which works on numbers.

(We cannot do the same in JavaScript, why?)

2. Generic Type Function

const id = x => x;

console.log(`${id(0)}`); // ==> 0

console.log(`${id("tirgul 2")}`); // ==> tirgul 2

The function id can be applied on any value - for example: string, boolean, number, but also arrays and maps.

We mark its argument as a type variable T1 and the type of the function is:

<T1>(x: T1) => T1

NOTE: This is the most basic example of a polymorphic function - also called a generic function.

NOTE: Defining this identity function as <T1>(x: T1) => T1 is very different from defining it as

(x: any) => any. Can you explain why? Give examples of functions to illustrate.

NOTE: To mark a function as generic in TypeScript, we must use the syntax:

function id<T>(x: T): T { return x; }.

3. Union Type Function

Consider this function:

let unionFunc = x => {

if (x === 0) return 0;

else return false;

};

console.log(`${unionFunc(0)}`); // ==> 0

console.log(`${unionFunc(5)}`); // ==> false

NOTE: the function can return two different types.

How can we describe its type?

One weak description is to use: (x: number) => any.

A more informative description would be to use a type union:

<T1>(x: T1) => number | boolean.

Note that we could infer that x is of type number because we compare it to 0.

But the operator === is a universal operator in JavaScript and does not require its parameters to be of the same type. In other words, the primitive === has type: (x: any, y: any) => boolean.

NOTE: Do we want to define functions which return union types of this sort?

Answer: This is not a good idea. Such functions are surely not defined well if their return value must be described by a complicated type of this sort - it is almost always the sign of a bug.

Such return values are very complicated to consume - if we want to call this function, we must always test the return value as:

let x = unionFunc(2);

if (typeof x === "number")

return x + 2;

else

return 0;

and we will almost never be able to invoke g(unionFunc(2)) for usual functions.

4. Map Function Type

We can apply map (of the ramda package) on varied arguments:

import { map } from "ramda";

let numbersArray = map(x => x + 1, [1, 2, 3]);

let stringsArray = map(x => x + "d", ["a", "b", "c"]);

console.log(numbersArray); // ==> [ 2, 3, 4 ]

console.log(stringsArray); // ==> [ 'ad', 'bd', 'cd' ]

map receives two arguments: a function and an array.

Let us name them func and array.

array can contain items of any type - let us mark it as T1 under the assumption that the array is homogeneous.

func gets one parameter - which must be of the type of the elements in array.

For each item in array it returns a value of a given type - let us call this return type T2.

The type of the parameter func is therefore: (x:T1)=>T2.

The value returned by map is an array of the values returned by func - that is, its type is T2[].

Putting all the elements together: the type of the map function is:

<T1, T2>(func: (x: T1) => T2, array: T1[]) => T2[]

5. Filter Function Type

We can apply filter (of the ramda package) on varied arguments:

import { filter } from "ramda";

let numbersArray = filter(x => x % 2 === 0, [1, 2, 3]);

let stringsArray = filter(x => x[0] === "d", ["david", "dani", "moshe"]);

console.log(numbersArray); // ==> [ 2 ]

console.log(stringsArray); // ==> [ 'david', 'dani' ]

So what should be the type of the filter function?

filter receives two parameters: a function pred and an array.

array can contain items of any type - let us call it T1 under the assumption that the array is homogeneous.

pred is a function, that gets one parameter of type T1 and returns a boolean value.

filter returns a sub-array of the original array, so that the type it returns is T1[].

Putting all elements together, the type of the filter function is:

<T1>(pred: (x: T1) => boolean, array: T1[]) => T1[]

6. Reduce Function Type

We can apply reduce (of the ramda package) on varied arguments:

import { reduce } from 'ramda'

let num = reduce((acc, curr) => acc + curr, 0, [1, 2, 3]);

let count = reduce((acc, curr) => acc + curr.length, 0, ["a", "bc", "def"]);

console.log(num); // ==> 6

console.log(count); // ==> 6

So what should be the type of the reduce function?

reduce receives 3 arguments:

- The reducer function

reducer - The initial value

init - The

array

The elements of array can be of any type - let us call it T1 under the assumption that the array is homogeneous.

reducer gets two parameters (acc and curr) and outputs a value that will be the acc at the next iteration.

curr is one of the items of array at each iteration.

We infer that:

currmust be of typeT1(same type as the elements inarray)accandinitmust be of the same typeT2reduceris of type:(acc: T2, curr: T1)=>T2.

reduce eventually returns the last value of acc returned by reducer - so the type of the return value should be T2.

Putting all things together, the type of reduce is:

<T1, T2>(reducer: (acc: T2, curr: T1) => T2, init: T2, array: T1[]) => T2

7. Compose Function Type

Compose receives two function arguments f and g and returns a new function as a value:

import { compose } from 'ramda'

let hn = compose(y => y * y, x => x + 1);

hn(3); // ==> (3 + 1) * (3 + 1) = 16

// Reverse a string:

// - Make an array of chars out of the string (split(""))

// - Reverse the array

// - Join the chars back into a string array.join("")

const reverse: (s: string) => string = s => s.split("").reverse().join("");

reverse("abcd"); // ==> 'dcba'

// Return a new string with all upper case chars

const upper: (s: string) => string = s => s.toUpperCase();

upper("abcd"); // ==> 'ABCD'

let upperReverse: (s: string) => string = compose(reverse, upper);

upperReverse("abcd"); // ==> 'DCBA'

What is the type of the function compose?

The first parameter f receives a value of any type, let us call it T1 and returns a value of any type T2.

The second parameter g receives a value of any type, T3 and returns a value of any type T4.

The returned value is a function which computes f(g(x)) for any parameter x.

We infer that the returned function must receive parameters of the same type as g - that is T3.

In addition, we infer that the value returned by g(x) must be of the type that f expects - that is, T4 must be the same as T1.

Finally, the value returned by f(g(x)) is of the same type as that returned by f - that is, T2.

Putting all things together - the type of compose is:

<T1, T2, T3>(f: (y: T1) => T2, g: (x: T3) => T1) => (x: T3) => T2;

It helps to renumber the type variables according to the order in which they are computed:

<T1, T2, T3>(f: (y: T2) => T3, g: (x: T1) => T2) => (x: T1) => T3;

which can be read as: a value x of type T1 is mapped to a value of type T2 and then to a value of type T3.